Why Smart Kids Still Struggle

And How to Foster Long-Term Success

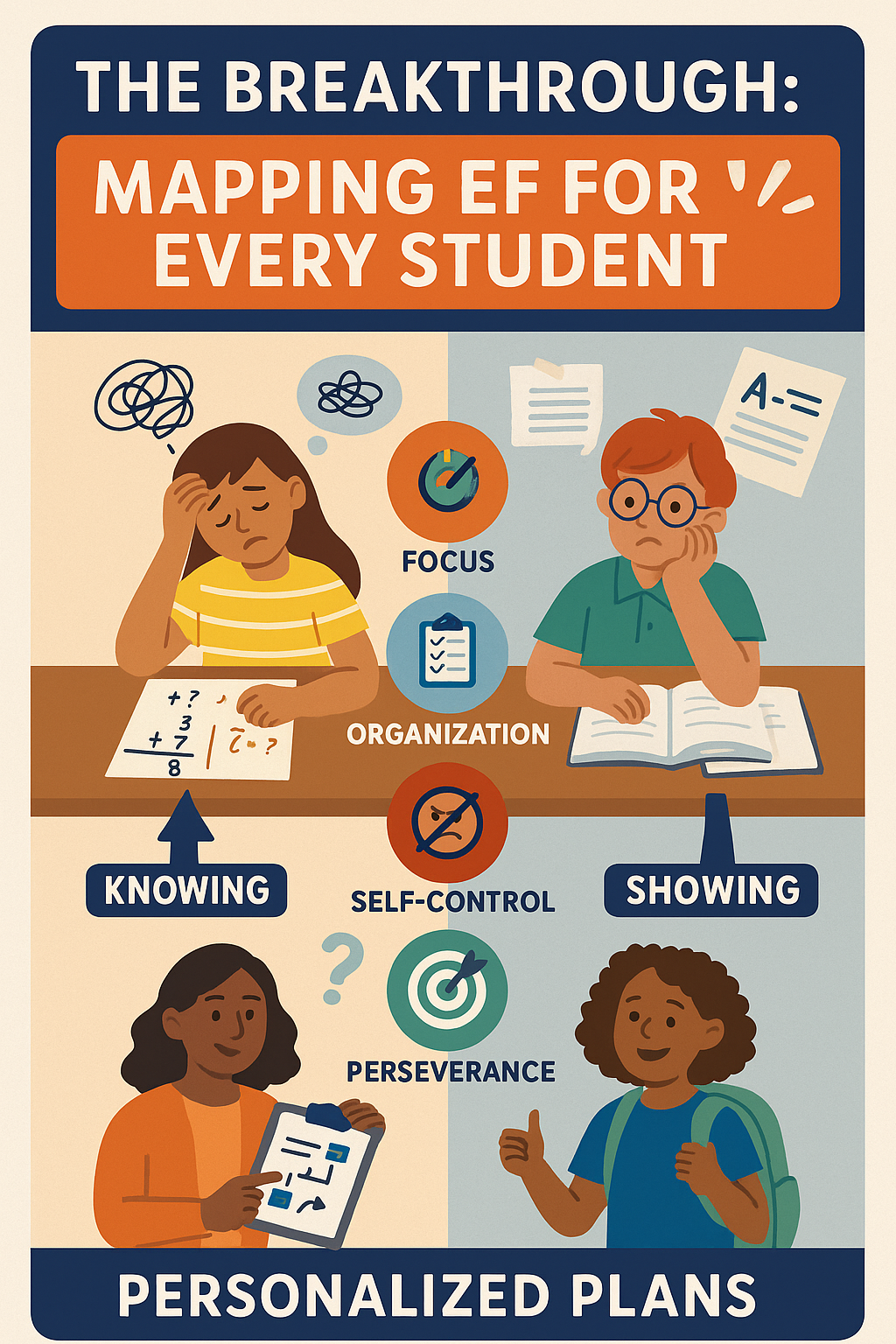

It’s natural to imagine the hardest part of school will be academics—reading, math, spelling tests. But ask any teacher, and they’ll tell you: the real hurdle isn’t content at all. It’s executive function (EF)—the skills that drive focus, organization, self-control, and perseverance.

EF is what turns knowing into showing. A child may grasp math concepts quickly but stall on a multi-step word problem. Another may read fluently but constantly lose track of their work. Without EF, knowledge doesn’t translate into success.

That’s why at WHPS, we treat EF just like reading or math. We break it into measurable skills, help students prioritize the single most impactful goal for growth, and weave practice into every classroom routine.

This year, we’re especially excited to launch new EF and social-emotional skill progressions that help teachers and students identify, name, and work on a personalized high-impact goal. These progressions will be part of Student-Led Conferences (SLCs), giving every child a concrete roadmap for growth.

(Click below to explore how EF and SEL come to life at WHPS.)

-

Below is a simplified overview of the EF and social-emotional skills students develop over time. It’s designed to give families the big picture.

At Student-Led Conferences (SLCs), each child will use a zoomed-in grade-level version of this progression to:

Reflect on strengths

Identify one high-impact area for growth

Set a clear, meaningful goal for the semester ahead

This work has been a passion project of mine since graduate school, and it’s exciting to bring it to fruition for students and families in a way that makes growth visible and actionable.

-

Many families come to us already knowing their child is bright—but “bright” can mean very different things. A child might be (in somewhat generalized terms):

Academically advanced: working above grade level in one or more subjects, often with strong support and reinforcement.

Gifted: demonstrating advanced reasoning, creativity, or problem-solving across domains, often paired with heightened sensitivity or intensity.

Highly gifted: showing extraordinary ability far beyond typical developmental expectations, sometimes 3+ years ahead in cognitive domains.

These profiles may sound similar, but they are quite distinct and require different approaches in the classroom.

One thing many of these children share is what we call the gifted paradox. Recent brain research—and what we see every day in our classrooms—shows that the higher a child’s IQ, the more gradually executive function (EF) tends to develop. This mismatch—soaring intellect paired with slower-developing EF—creates a complex learning profile.

It can be a bit like having the engine of a race car inside a frame that’s still being built: the potential is extraordinary, but the supports need to catch up before the car can really take off. In the same way, gifted learners may be able to think far beyond their years, but still need time and practice to develop the stamina, organization, and regulation required to consistently show what they know.

At WHPS, we are uniquely equipped to support this profile by challenging advanced thinkers while also building the EF and literacy skills that unlock their potential. Our approach ensures children don’t just carry brilliant ideas in their heads—they learn how to apply, express, and extend those ideas with confidence.

In first grade especially, there are three areas we are carefully balancing for long-term success:

Executive Function (EF): skills like focus, stamina, organization, and self-regulation.

Cognitive Abilities: the advanced reasoning and problem-solving parents often see at home.

Reading & Writing Skills: the output children need to demonstrate what they know in a classroom setting.

Even when a child can multiply large numbers in their head, math is not only about solving algorithms—it also requires reading problems, interpreting multi-step directions, and showing work clearly. Similarly, many gifted learners are the first to share passionately in class, but may struggle to respond directly or succinctly.

At WHPS, we support all of these areas. A big part of our work is helping children learn how to channel and focus their thinking so their ideas come through clearly. This is woven into the school day in ways that may not always be obvious from the outside. For example, during Morning Meeting, students practice sharing in structured ways. Teachers introduce sentence frames and guided prompts that help students organize their thoughts, respond directly to a question, and connect their ideas to what others have shared. A student might use a frame like, “One detail I noticed is…” or “My idea connects to…”—simple tools that build habits of clarity and focus.

These experiences do more than improve classroom discussion. They strengthen the executive function, communication, and output skills that are just as critical as raw ability. Combined with intentional scaffolding in reading, writing, and problem-solving, this creates a wraparound learning environment where gifted children grow in a balanced way. The result is that bright ideas don’t just stay in their heads—they become skills that can be communicated, applied, and extended in meaningful ways.

While every student develops at their own pace, these three strands—EF, cognitive abilities, and reading/writing—tend to come into much closer alignment as children transition into second grade. That’s why our multi-age Upper Elementary program begins at this stage: it’s the point where students are typically ready to accelerate in both thinking and output.

It takes patience to keep the foot on the academic accelerator while nurturing still-developing EF and literacy. But with the right support, the payoff is remarkable: students grow into learners who can not only think deeply but also apply their intelligence in lasting, independent ways.

-

If a child can’t show what they know—even with gentle prompting and scaffolding—they can’t truly apply their knowledge. That’s why we take a close look at each student’s strengths and make thoughtful decisions about their learning goals. But intelligence alone isn’t enough; without executive function, being “smart in isolation” doesn’t lead to growth.

EF shows up everywhere academics do:

Organizing thoughts in writing

Starting math without stalling

Shifting smoothly between subjects

Planning long-term projects

Recovering from mistakes

Collaborating with peers

Without EF, even the brightest learners hit roadblocks. With EF, knowledge gains traction and learning sticks.

-

We don’t treat EF as an “extra.” It’s built into the fabric of school life:

Morning Meetings & Friendship Circles model reflection and problem-solving.

Writer’s Workshop develops planning, revising, and persistence.

Structured reset times teach children how to regulate and rebound.

Leadership Notebooks help students set academic and EF goals, tracking growth across the year.

At every age, children practice EF in real-life contexts—because skills grow fastest when they’re modeled, practiced, and applied daily.

-

You don’t need to reinvent the wheel—many of the same tools your child uses at school work beautifully at home:

Checklists: 2–3 items (pictures for younger kids)

Predictable routines: Label spots for shoes, homework, or sports gear

Daily responsibilities: Let your child pack their lunch or backpack—independence grows when they “own” the cycle

Normalize mistakes: Try, “That didn’t work yet—what’s another way?”

Movement & mindfulness: Borrow resets from school—a stretch, a short walk, or a breathing break

Binary choices: Offer two options instead of open-ended battles (“Homework now or after snack?”)

Quiet time: Create a short pause each day for reading, journaling, or just being still

As I often remind students and families, EF isn’t about perfection—it’s about practice. Skills grow when children have consistent chances to try, reflect, and reset.

Children need both scaffolds and space: scaffolds so they know what’s expected, and space so they can practice independence without fear of failure. That balance—at school and at home—gives EF the room to take root. And remember: even when children know the strategies, they need the emotional bandwidth to use them. That’s why EF connects directly to the body budget (see our recent blog on that topic).

🌱 The Payoff: Resilience That Lasts a Lifetime

At WHPS, these skills are lived and practiced every day. By combining daily routines with EF/SEL progressions and student ownership through SLCs, every child has a plan, and every parent has a window into their child’s growth.

In real time, these habits fuel academic leaps and stronger social connections. But research also shows that when EF is nurtured from a young age, it predicts long-term success—greater likelihood of finishing college, stronger earning potential, and even healthier adult relationships.

We take deep pride in fostering these skills in meaningful ways and in helping parents play an active role in the journey. When students learn to manage frustration, persist through challenges, and reflect on their growth, they don’t just succeed in school—they build the foundation for a thriving future. That’s the power of executive function in action.